Teaching Inferences: 10 Amazing Books for Teaching Kids to Infer

Once students learn how to make inferences, reading will become much more enjoyable and fulfilling! At the beginning stages of inferring, students might look at the pictures and explain what is happening. That is a great starting point, but, as teachers, we want them to progress far beyond that. Ideally, they will eventually be able to make inferences by combining what they see and read in the text with their personal background knowledge.

Below I have highlighted ten books that are wonderful for using in conjunction with strategies to teach inferencing. It is a diverse group of stories-- some are wordless, others are silly, and some contain mature themes that will require a bit of analysis to unpack. In the past, I have struggled to explain the difference between making inferences and making predictions. It isn’t easy because they are quite similar yet not interchangeable. I found this article helpful to review before planning my lessons in order to strategize how to teach both skills successfully.

Please note that this post contains affiliate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Tips for Teaching Inferences

1. Teach about Schema (Background Knowledge)

Before I begin teaching my students about inferences, I always start by introducing the concept of “schema.” Schema is the background knowledge we have about things in the world around us. I like to bring a lint roller to school on the day we talk about schema to show my students how “sticky” our brains can be. When we move around the world in our daily lives, we’re picking up different pieces of information with our lint rollers (brains) and storing them away for later. We all have different lived experiences, so everyone’s schema will be a little bit different. We practice activating our schema with slides like the one below!

2. Connect Schema with Text Clues

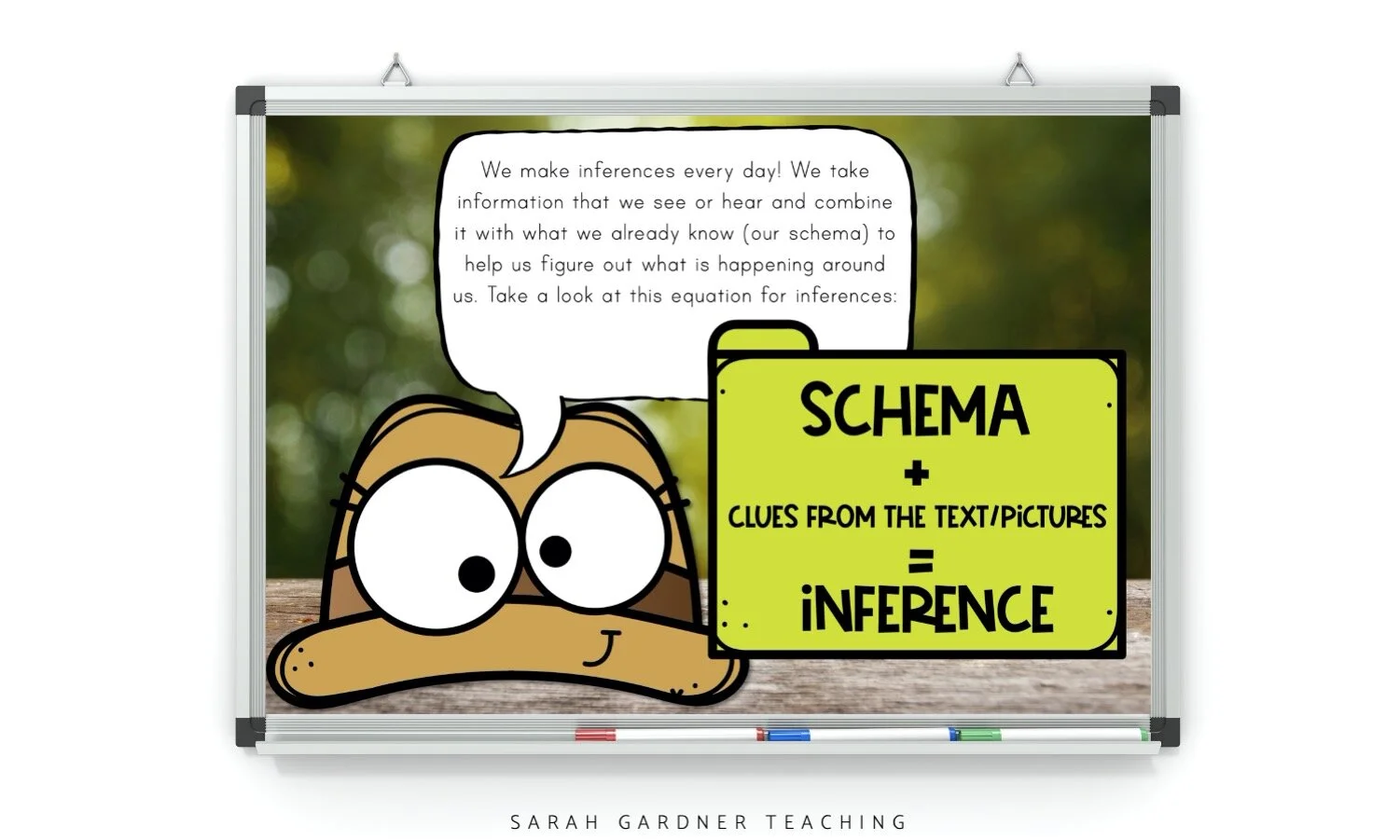

Next, I teach students the “formula” for making inferences. I like to break it down like this for students so they can really get a good visual of what is going on inside their brain when they make an inference. It looks like this:

SCHEMA + TEXT CLUES = INFERENCE

Once we learn this formula, we put on our “detective” hats to practice making inferences with pictures. We find the “clues” in each picture and connect them with the schema we have stored in our brains. For example, the woman in the picture below is wearing a white dress and holding a bouquet of flowers. The schema we have about bouquets and white dresses is that brides usually wear a white dress and hold a bouquet on their wedding day. We can put these clues together with our schema to infer that this is a picture of a woman on her wedding day.

3. Practice Finding “Clue” Words

After practicing with several pictures, we move on to finding clue words within text to help us make inferences about what is. going on in a short passage.

Want to take a closer look at the no-prep mini-lesson I use to teach inferences? Click here!

BOOKS FOR TEACHING INFERENCES TO KIDS

Flora and the Flamingo by Molly Idle

Flora and the Flamingo is an adorable wordless story that is a great starting block to teach students how to make inferences. The book is the story of a young girl dressed in a tutu and a flamingo making varying poses. The illustrations in this book are significant because there is no text. The pictures give you plenty of material to draw inferences from, without being crowded with distractions. Your littles will love this book! It would also be fun to do a yoga brain break at the end of this lesson because a lot of their poses in the story look like they’re doing yoga. YouTube has some awesome yoga brain break options for free, or you can check out my yoga pose cards here.

Sylvester and the Magic Pebble by William Steig

This bittersweet book is a crowd-pleaser every time I read it. Sylvester is a donkey that likes collecting pebbles. One day he finds a magic pebble, which is so exciting for the donkey! Shortly after finding it, a lion approaches, and he wishes he were a rock to protect himself. Now a rock, Sylvester is unable to turn back into a donkey because he has to be holding the magic pebble to make a wish. A lot of time passes and Sylvester’s parents are heartbroken that he is gone. One afternoon they decided to have a picnic and just so happen to set it up on the rock that is Sylvester. His dad finds the magic pebble and sets it on the rock. Sylvester makes a wish to turn back into himself, and the family is reunited. This is such a lovely story and it is easy to get swept up in the plot and forget that we can use it as a teaching tool. If you do, I think you will find that the element of magic makes the process of making inferences even more fun for the students!

Tar Beach by Faith Ringgold

Tar Beach was published in 1991 and somehow I just came across it recently, even though it won many awards in its time. It is a fascinating story about eight-year-old Cassie, who shows us the city by flying above the buildings and explaining their significance. It has a captivating narrative, and deep topics are discussed-- such as race and the ability to join unions. There is a quote at the end that stuck out to me that reads, “It’s very easy to fly. All you need is to have somewhere to fly you can’t get to any other way.” This book is a stellar example of magic realism and I guarantee your students will love it.

Small in the City by Sydney Smith

The first thing I was drawn to about this book was the realistic and delightful illustrations, and then the story took me completely by surprise. The premise is that the narrator is giving someone unknown advice about faring well in the big city. He shares knowledge on listening to music, using alleys as shortcuts, etc. The reader can’t help but wonder who he is talking to. Toward the end of the book, one of the pictures shows the small boy putting up a poster for his missing pet, and you realize that all of the words of wisdom are directed toward his dog. I’ve read some sad stories, but this one hit hard! Many students will relate to it, and wondering who the narrator is speaking to leaves plenty of room for making inferences.

Knock Knock: My Dad’s Dreams for Me by Daniel Beaty

This is a beautiful but intense story about a little boy who has a great relationship with his dad. Every morning his dad wakes him up by playing a knock-knock game with him. The child is saddened when his father stops coming to his room in the morning and no longer lives with him. The boy decides to write a letter to his father and leave it on his desk just, in case his father is there during the day when he is not. He explains how much he misses him and wonders who will teach him to do things such as shaving when he’s older. A while later, the child receives a response from his father explaining that he won’t be coming home. He gives answers to all of the questions he asked in the first letter and some additional advice. This story is deep and brings up some big questions about life. This story might not be right for every group of children and would be best suited for upper-elementary kiddos.

Dirt + Water = Mud

Many of the books on this list have been rather serious, but Dirt + Water = Mud is a lighthearted breath of fresh air. The story is about a girl and her dog, and each page shows the pair of pals doing something else in the form of a math equation. It’s all very silly, but a great time to make inferences with littles because most of them will have sufficient background knowledge to predict how the equation will be solved. For example, knowing that if you put water in the dirt, it makes mud.

They All Saw a Cat by Brendan Wenzel

They All Saw a Cat is a very interesting story about how perspective shapes what we see. The text takes us through a list of creatures (child, dog, fox, etc) that all saw a cat based on his whiskers, ears, and tail. The author uses a lot of repetition in this story, which in my opinion makes it ideal for introducing this topic to young students.

What Do You Do with a Tail Like This? by Steve Jenkins

Elementary students of any grade level will adore this story. Many animals are highlighted, and each one has a unique quality or body part. The reader is asked what they think the animal does with that body part, which makes it an ideal read-aloud because it provides natural stopping points to think about our previous knowledge of that animal, consider what other details we have already learned about that creature, and then make an inference. I can say that I definitely learned interesting facts I didn’t know before. This text would also make a great cross-curricular tie in with your study of animal adaptations!

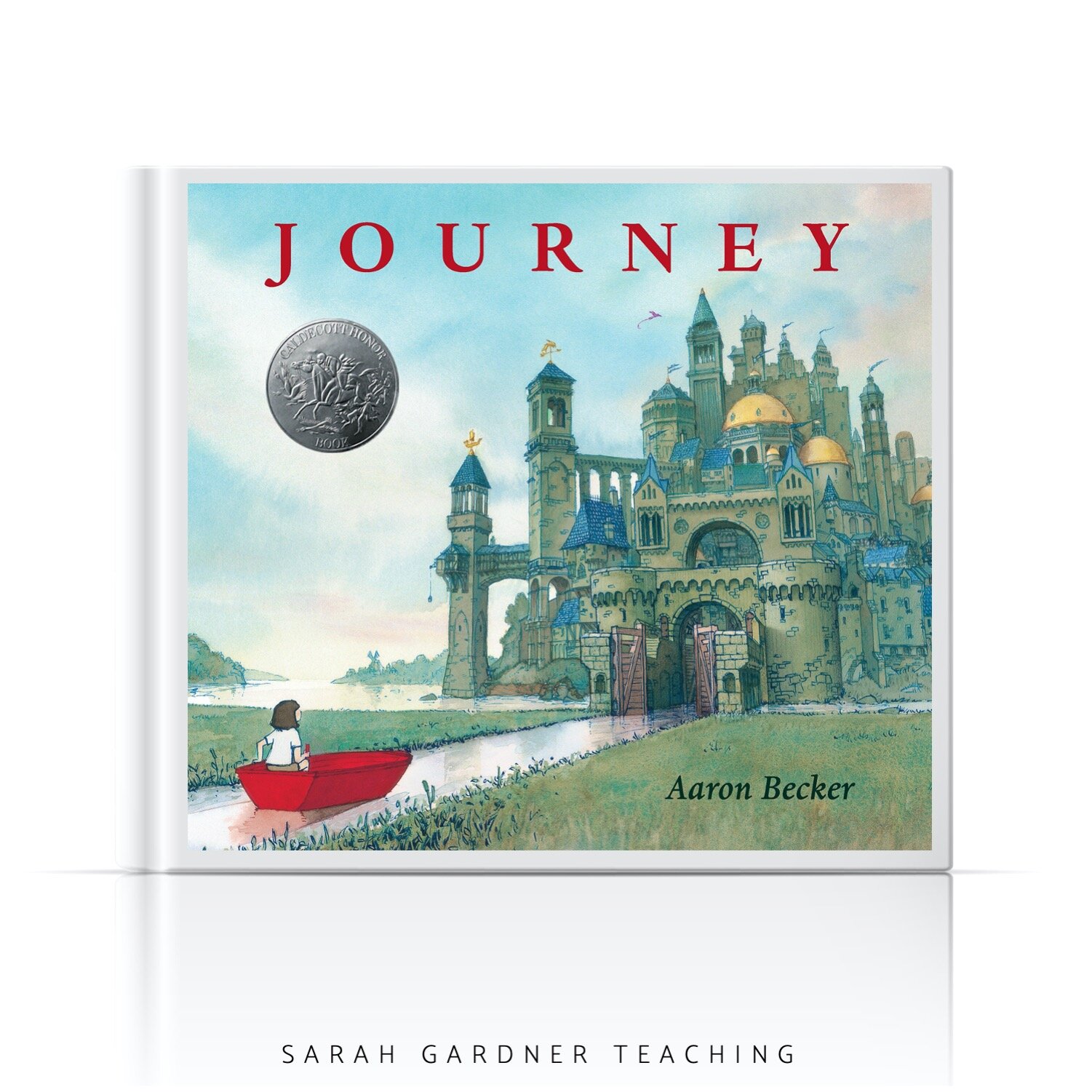

Journey by Aaron Becker

Journey is one of the most unique children’s books I’ve ever used in a lesson. It is a wordless book, which is creative in itself. However, this book stands out because illustrations are extremely detailed without giving one set narrative that the reader is supposed to see. I could read this book with various groups of kids, and I am confident that each group would come up with a story that differs completely from every other group. It is perfect for the intersection of creativity and making inferences. If you have students that struggle cultivating creativity, this might be a little uncomfortable at first. Modeling the first few pages of the story to show them how it can be done would be a valuable tool. If you like Journey, it is the first book in a trilogy, so I urge you to check out the other two books as well!

This is Not My Hat by Jon Klassen

I’ll be honest, I wasn’t too fond of this story the first time I read it. It is about a whale that stole a hat from another fish. He explains that he knows it’s wrong but that he was going to keep it anyway. He is on a journey to go off to a secret place with tall plants, where he won’t be found. The book has a very mysterious vibe and is not the usual kind that I would gravitate toward. Still, it is an excellent tool for practicing making inferences based on the text because it leaves a lot of questions unanswered.